9. Plague, Heresy and the Seeds of Reformation

| Key Dates # |

|

|---|

| 1300s | The Black Death. 1/3 of the population from India to Iceland is wiped out

|

| 1309 | Beginning of the so-called "Babylonian Captivity of the Church"

|

| 1314 | Grand Master of the Knights Templar, Jacques de Molay, executed (following show trials that led to Templars across France being put to death)

|

| 1316 | Raymund Lull, missionary to North Africa is stoned to death

|

| 1328 | John Wycliffe, English reformer, born

|

| 1337 | Beginning of the Hundred Years War between England and France

|

| 1371 | Jan Huss, Bohemian reformer, born

|

| 1377 | End of the "Babylonian Captivity"

|

| 1378 | The Great Schism. Pope Gregory XI moves the papacy back to Rome. King Francis I

of France declares Clement VII Pope in Avignon. There are two competing popes

for close to 40 years

|

| 1380 | Thomas a Kempis, author of Imitation of Christ born

|

| 1415 | Council of Constance condemns Wycliffe; subsequently burns Jan Huss

|

| 1417 | Council of Constance deposes both popes and elects a new one, ending the Great Schism

|

| 1431 | Birth of Pope Alexander VI, a seriously corrupt Pope

|

| 1452 | Savonarola born. He taught the authority of scripture and understood the shortcomings of the Church, but was a tough ruler

|

| 1453 | End of the Hundred Years War

|

| Fall of Constantinople

|

| 1478-1834 | Spanish Inquisition

|

| 1483 | Martin Luther, German reformer, born

|

| 1492 | Erasmus ordained. Humanist movement begins to stir members of the church to moral reform

|

| Fall of Muslim Granada to the Catholic Kings of Spain, Ferdinand and Isabella; end of the Reconquista

|

| Columbus sails from Spain in search of a western route to the Indies

|

| Jews converted or expelled from Spain, their assets are seized

|

| 1497 | Philip Melanchthon, German reformer, born

|

| 1498 | Savonarola executed in Florence

|

Overview

Europe in 1300 was rapidly expanding. It was increasing in intellectual and mathematical

sophistication. Technically, thanks to water power and the mechanical discoveries that flowed

from it, Europe was in the midst of what many historians call the Medieval Industrial Revolution.

There was, however, a major break between the Middle Ages and what became known as the

Renaissance (lit. "rebirth").

- The 14th Century was a time of turmoil, loss of confidence in institutions (including the

established church), and feelings of helplessness in the face of events occurring elsewhere in

the world, and forces beyond human control.

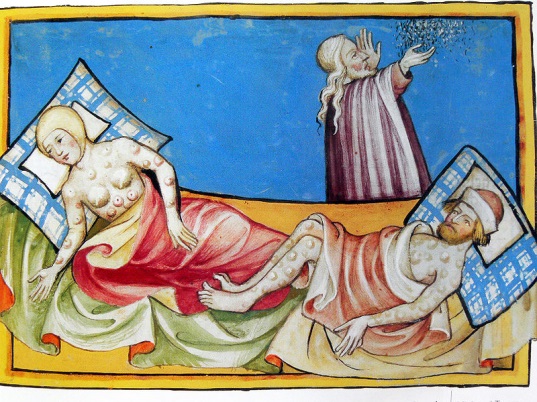

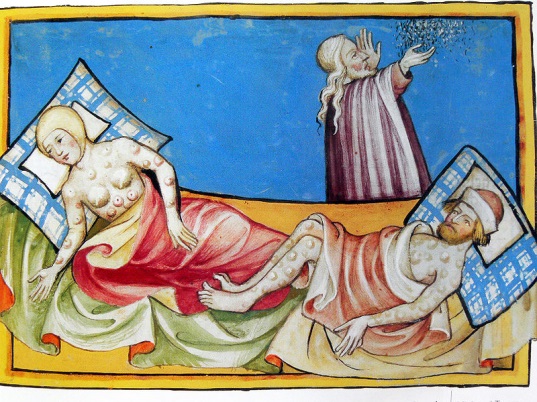

The Black Death

The Black Death (Bubonic Plague) was rampant during the 14th Century. It is believed that it

originated in China and travelled to Europe via the Silk Road or merchant ships. No one knows

how many people died, but numbers range from 70 to 200 million, or more than a third of the

total European population at the time. For example, 1.5 million people out of an estimated

total of 4 million died in England alone in just three years between 1348-1350. The plague also

had a major impact on England's social structure, contributing to the Peasants Revolt of 1381,

and led to the power of established religion being undermined, opening it up for reformation.

The Black Death was caused by fleas carried by rats that were common in towns/cities. The

fleas bit their victims, injecting them with the disease. Death could be very quick for weaker

victims. The first signs of the plague were lumps (or buboes) in the groin or armpits. After this,

livid black spots appeared on the arms and thighs and other parts of the body. Few recovered.

Almost all died within three days, usually without any fever. Many people were thrown into

open communal pits. The oldest, youngest and poorest died first. Other died from personal

contact with the sick (septicemia) or water droplets through coughing or sneezing (pneumatic).

Entire villages simply ceased to exist. Jews, friars, foreigners, beggars, pilgrims and lepers were

blamed and persecuted, adding to widespread fear and misery; in Spain, Arabs were suspected

of spreading plague. In towns people lived close together, in unhygienic conditions, and knew

nothing about contagious diseases. The disposal of bodies was crude and helped to spread the

disease further as those who handled dead bodies did not protect themselves in any way. The

filth that littered streets gave rats the perfect environment to breed and increase their number.

Lack of medical knowledge meant that people tried anything to help them escape the disease.

One of the more extreme was the flagellants (especially in Germany), who travelled from town

creating enthusiasm, showing their love of God by whipping themselves, hoping that He would

forgive their sins and that they would be spared. Others carried flowers hoping that the

perfume would ward off bad "humours" that were thought to spread disease.

People dying of plague (note the buboes)

Flagellants hoping to escape the Black Death

The Black Death had a huge impact on society. Fields went unploughed as labourers died.

Entire villages faced starvation. Towns and cities experienced food shortages as the villages that

surrounded them could not provide them with enough food. Feudal lords lost their manpower to

disease and turned to sheep farming as this required fewer labourers. The crime rate across

many European cities soared, as people case off restraint, abandoned order and traditional

moralities because they believed they were doomed anyway.

Grain farming became less popular, keeping towns and cities short of such basics as bread. This

led to inflation - the price of food went up, creating more hardship for the poor. In some parts

of England, food prices went up by four times, even though this was outlawed in some countries.

Feudal law stated that peasants could only leave their village if they had their lord's permission.

Now many lords were short of desperately needed labour for the land that they owned.

Peasants demanded higher wages as they knew that the lords were desperate to save harvests.

Some Governments banned price increases and peasants travelled in search of better paid work,

with or without permission.

Though some decided to ignore the statutes, many knew that disobedience would lead to serious

punishment. This created great anger amongst the peasants which was to boil over in England in

1381 with the Peasants Revolt.

In terms of the role of the church, it was considered essential that victims be given the last rites

and have the opportunity to confess their sins before they died. There were not enough clergy

to offer the last rites or give support. Pope Clement VI was agreed to grant remission of sins to

all who died of the Black Death. Victims were allowed to confess their sins to one another, or

"even to a woman".

The first wave of the Black Death swept through Europe in 1347-1350 and there were six more

waves between 1350 and 1400. Other localized plagues occurred over the following centuries.

The Black Death was a major challenge for the prestige and spiritual authority of the organized

Church, while at the same time there was a marked growth in religious enthusiasm and birth of

marginal groups. The church could offer no reason for the deadly disease and beliefs were

tested. People started questioning religion and such doubts ultimately led to reformation

movements.

Some Influential Christians During This Period

John Wycliffe (1328-1384)

Wycliffe was born in England, 320 kilometres from London. He entered Oxford University in

1346, but because of periodic eruptions of the Black Death, was not able to earn his doctorate

until 1372. By then he was considered the leading philosopher and theologian in Oxford, the

most prestigious university in Europe.

His attitudes to the Catholic Church frequently got Wycliffe into trouble, and he was brought to

London to answer charges of heresy; the event broke up in acrimony. Three months later, Pope

Gregory XI issued five bulls against Wycliffe, in which he was accused on 18 counts and was

called "the master of errors." At a subsequent hearing before the archbishop at Lambeth Palace,

Wycliffe replied, "I am ready to defend my convictions even unto death.... I have followed the

Sacred Scriptures and the holy doctors." He went on to say that the Pope and the Church were

second in authority to Scripture. "The only head of the Church is Christ."

Because of Wycliffe's popularity in England, jealousy and a split in the papacy (the Great Schism

of 1378, when rival popes were elected), Wycliffe was put under "house arrest", forced out of

Oxford and left to pastor his Lutterworth parish. He trained and organized preachers who

travelled evangelizing.

Wycliffe deepened his study of Scripture and wrote more about his conflicts with official church

teaching, including transubstantiation; indulgences; Purgatory, pilgrimages, worship of saints

and veneration of relics, and the confessional ("Private confession ... was not ordered by Christ

and was not used by the apostles.") He taught that Christians did not need a priest to mediate

with God for them. He reiterated the biblical teaching on faith: "Trust wholly in Christ; rely on

his sufferings; beware of seeking to be justified in any other way than by his righteousness." He

rejected the Church's claim to infallibility.

Believing that every Christian should have access to Scripture (only Latin translations were

available at the time), Wycliffe began translating the Bible into English, the first such. This was

opposed by the official church: "By this translation, the Scriptures have become vulgar, and they

are more available to lay, and even to women who can read, than they were to learned scholars,

who have a high intelligence. So the pearl of the gospel is scattered and trodden underfoot by

swine." Wycliffe replied, "Englishmen learn Christ's law best in English. Moses heard God's law

in his own tongue; so did Christ's apostles."

Wycliffe died before the translation was complete (and before authorities could convict him of

heresy). Though his followers were driven underground; they remained a persistent irritant to

English Catholic authorities until the English Reformation made their views the norm.

Jan Huss (1370-1415)

Huss was the most important 15th-century Czech religious Reformer, who came to prominence

because he questioned the infallibility of the established church. He was ordained a priest in

1401 and taught in Prague. Huss stressed the role of Scripture, defined the church as the Body

of Christ, and taught that only God can forgive sin. He opposed pilgrimages. He condemned the

corruption of the established church and clergy. He strong opposed indulgences. He held that

all Christians, not just priests, should receive both bread and wine at Communion. Huss was also

embroiled in the bitter controversy of the Great Schism (1378-1417).

Huss' work was transitional between the medieval and the Reformation periods and anticipated

the Lutheran Reformation by a century.

The writings of Wycliffe had stirred his interest in the Bible. Czech Christians, including Huss,

agreed with Wycliffe's reforming ideas (Huss translated Wycliffe's denunciations against the

Catholic Church into Czech); though they had no intention of changing traditional doctrines,

they wanted to place more emphasis on the Bible, expand the authority of church councils (ie

lessen that of the Pope), and promote the moral reform of clergy. Huss began increasingly to

call on his followers to trust the Scriptures, "desiring to hold, believe, and assert whatever is

contained in them as long as I have breath in me."

The situation was complicated by European politics, as two popes vied to rule all of

Christendom. A church council was called at Pisa in 1409 to settle the matter. It deposed both

popes and elected Alexander V as the legitimate pontiff. Alexander was "persuaded" to side

with Bohemian church authorities against Huss. Huss was forbidden to preach and was

excommunicated, but he continued to preach.

When Alexander V's successor, the antipope John XXIII (1370-1419), authorized the sale of

indulgences to raise funds for a crusade against a rival, Huss declared that he could no longer

justify the pope's authority. He leaned heavily on the Bible, as the church's final authority.

Huss' excommunication was revived, and an interdict was put upon the city of Prague: ie no

citizen could receive Communion or be buried on church grounds as long as Huss continued his

ministry. Huss withdrew to the countryside toward the end of 1412. He spent the next two years

writing and outlining his doctrinal beliefs. Many of his books were subsequently burned in

Prague. Huss rejected indulgences and taught that Christ is the head of the Church.

In November 1414, the Council of Constance (in Germany) assembled, and Huss was urged by

Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund to participate and give an account of his doctrine. Promised

safe conduct, and because of the importance of the council (which had foreshadowed church

reforms), Huss went. When he arrived he was arrested (the Emperor was told "It is not

necessary to keep one's word to a heretic"), and he remained imprisoned for months. Instead of

a hearing, he was eventually brought before authorities in chains and asked to recant his views.

When he saw he wasn't to be given a forum for explaining his ideas, let alone a fair hearing, he

said, "I appeal to Jesus Christ, the only judge who is almighty and completely just. In his hands I

plead my cause, not on the basis of false witnesses and erring councils, but on truth and

justice." On 6 July 1415, he was taken to the cathedral, dressed in his priestly garments, and

then stripped of them one by one. He refused one last chance to recant, at the stake, where he

prayed, "Lord Jesus, it is for thee that I patiently endure this cruel death. I pray thee to have

mercy on my enemies." He was heard reciting the Psalms as the flames engulfed him.

Following Huss' execution, Bohemian church leaders rejected the council and refused to submit

to the Holy Roman Emperor or the Pope. Attempts to subdue them by force were unsuccessful.

There was reconciliation eventually, but splinter groups remained, including a "Hussite"

community that became known as the Moravian Brethren, influential later in the conversion of

John and Charles Wesley.

Early in his career as a monk, Martin Luther discovered a volume of sermons by Huss. "I was

overwhelmed with astonishment," Luther later wrote. "I could not understand for what cause

they had burnt so great a man, who explained the Scriptures with so much gravity and skill."

Huss on trial at Constance

Statue of Huss in Central Prague

Raymund Lull (1232-1315)

Raymond Lull was born at Palma, Mallorca. He earned a position in the king's court there. One

day a sermon inspired him to dedicate his life to working for the conversion of the Muslims in

North Africa. He became a Secular Franciscan and founded a college where missionaries could

learn the Arabic they would need in missions. He spent nine years as a hermit. During that time

he wrote on all branches of knowledge, a work which earned him the title "Enlightened Doctor."

Lull made many trips through Europe to interest popes, kings and princes in establishing special

colleges to prepare future missionaries. He achieved his goal in 1311 when the Council of

Vienna ordered the creation of chairs of Hebrew, Arabic and Chaldean at the universities of

Bologna, Oxford, Paris and Salamanca. At the age of 79, Lull went to North Africa in 1314 as a

missionary. An angry crowd of Muslims stoned him in the city of Bougie (in modern-day Algeria).

Genoese merchants took him back to Mallorca, where he died. He was beatified in 1514.

Lull had worked most of his life to help spread the gospel. Indifference on the part of some

Christian leaders and opposition in North Africa did not turn him from his goal. Three hundred

years later his work began to have an influence in the Americas. When the Spanish began to

spread Christianity in the New World, they set up missionary colleges to aid the work.

Thomas a Kempis (1380-1471)

German monk and writer and author of "The Imitation of Christ", possibly the best known

Christian book on devotion and outworking of Christian faith, ie learning day by day to live like

Jesus. The book is divided into four sections, three of which provide detailed spiritual

instructions: "Helpful Counsels of the Spiritual Life", "Directives for the Interior Life", "On Interior

Consolation"; the last section "On the Blessed Sacrament", is based on traditional Catholic views

about the Lord's Supper.

German monk and writer and author of "The Imitation of Christ", possibly the best known

Christian book on devotion and outworking of Christian faith, ie learning day by day to live like

Jesus. The book is divided into four sections, three of which provide detailed spiritual

instructions: "Helpful Counsels of the Spiritual Life", "Directives for the Interior Life", "On Interior

Consolation"; the last section "On the Blessed Sacrament", is based on traditional Catholic views

about the Lord's Supper.

Savonarola (1452-1498)

Italian Christian preacher and reformer, renowned for his clash with dictatorial rulers and a

corrupt clergy. After the overthrow of the Medici in Florence in 1494 by the French king,

Savonarola was the sole leader of the city, setting up a "democratic republic". He claimed that

he had been sent by God to renew Christianity in Italy. His chief enemies were the Duke of

Milan and Pope Alexander VI, who issued edicts against him, all of which were ignored.

Under Savonarola's rule, Florence was to be a Christian Commonwealth, of which God was the

sole sovereign, and His Gospel the law: strict rules were made for the repression of vice and

frivolity; gambling was prohibited; and the vanities of dress were restrained. Women flocked to

the public square to fling down their costliest ornaments and Savonarola's followers made huge

"bonfires of the vanities."

Savonarola's claims led to his being called in 1495 to answer a charge of heresy at Rome; when

he failed to appear he was forbidden to preach. He disregarded the order, but problems at

home increased. A conspiracy for the recall of the Medici failed, and five conspirators were

executed, but this generated greater opposition to Savonarola.

In 1497 Savonarola was excommunicated. This prevented him from performing as a priest.

However, he tended the sick monks during the plague and continued to preach. A second

"bonfire of the vanities" in 1498 led to riots; and at new elections the Medici party came to

power. Savonarola was again ordered to stop preaching, and he was denounced by a Franciscan

preacher, Francesco da Puglia.

He was arrested, tortured and brought to trial for falsely claiming to have seen visions and

uttered prophecies, for religious error, and for sedition. On 23 May 1498, Savonarola and two

Dominican disciples were hanged and burned in the main square of Florence.

Savonarola's approach to Christianity-based government (echoed in Calvin's later reign in

Geneva) demonstrate some of the hallmarks of an imposed theocracy.

Savonarola

Pope Alexander VI

Controversies

Papal Corruption

By the end of the Middle Ages the mission of the papacy had been corrupted by conflict between

its duties in leadership of the church community and its worldly responsibilities as head of the

Papal States.

Pope Alexander VI (one of the Borgia Popes) epitomizes this corruption. Born as Rodrigo Borgia

in Spain in 1431, he was elected Pope in 1492, an event that spawned rumours that he had spent

a considerable fortune bribing the Cardinals to assure his success. The continuity of the Church

of Rome provided some stability as Europe sank into barbarism. The new Pope loved the good

life. He sired at least twelve children through a number of mistresses. The most famous of his

offspring were his son Cesare, noted for the murder of political rivals, and his daughter Lucrezia

who was married off to a number of husbands for political gain.

Pope Alexander VI was in constant need of money - to support his lavish life style, to fill the

coffers for his political bribes and to fund his various military campaigns. The sale of

Cardinalships ("simony") was a major source of cash, so too was the sale of indulgences. An

indulgence was a written proclamation that exonerated - for a fee - the individual (or his

relatives) from punishment in the after-life for sins that had been committed, or in some cases,

may be committed in the future.

Fourteen years after his death, the corruption of the papacy that Alexander VI exemplified -

particularly the sale of indulgences - would prompt a young monk by the name of Martin Luther

to nail a summary of his grievances on the door of a church in Germany and launch the

Protestant Reformation.

"Babylonian Captivity of the Church"

The term "Avignon Papacy" refers to the Catholic papacy during the period 1309-1377, when the

popes lived in and operated out of Avignon, France, instead of their traditional home in Rome.

Philip IV of France was instrumental in securing the election of Clement V, a Frenchman, to the

papacy in 1305. This was an unpopular outcome in Rome. To escape the oppressive atmosphere,

in 1309 Clement chose to move the papal capital to Avignon. The majority of those whom

Clement V appointed as cardinals were French; since the cardinals elected the pope, this meant

that future popes were likely to be French, as well. All seven of the Avignonese popes and 111

of the 134 cardinals created during the Avignon papacy were French.

The Avignon popes were under the strong influence of the French kings. Some bowed to royal

pressure, as Clement V did to a degree in the destruction of the Templars. Although Avignon

belonged to the papacy, there was a perception that it belonged to France, and that the popes

were controlled by the French Crown.

Catherine of Siena and Bridget of Sweden are credited with persuading Pope Gregory XI to return

the Papacy to Rome. This occurred on 17 January 1377, despite objections by the cardinals in

France. The next Pontiff, Urban VI, was hostile to the cardinals; 13 of them chose another

pope, who opposed Urban. The "Western Schism", in which two popes and two papal curias

existed simultaneously continued for another four decades. The crisis damaged the prestige of

the papacy. Many in Europe were already facing crises of faith due to the Black Death. The gulf

between the Church and ordinary people widened.

Other Social Developments:- Leonardo da Vinci. Michelangelo. Machiavelli. Wars between

Italian city states. Age of Exploration commences. 1381 The Peasant's Revolt (30,000 angry

peasants descend on London). In 1453 the printing press was invented.

The Fall of Constantinople

The siege of Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire and one of the most heavily

fortified cities in the world, took place in 1453. Sultan Mehmed II, ruler of the Ottoman Turks,

led the assault. The city was defended by, at most, 10,000 men. The Turks had between

100,000 and 150,000 men on their side. (Historians agree such numbers can be exaggerated.)

The siege lasted for fifty days, after which the city was overtaken by the Turks. It was now

officially claimed for Islam and renamed Istanbul. The remaining Christians were allowed to

practice their religion, but had to dress in distinguishing attire and could not bear arms.

The siege of Constantinople

Sultan Mehmed II

The Hundred Years War (1337-1453)

The Hundred Years War was a series of conflicts between England and France about power, the

French crown, dynasties/succession, national honour, economic competition, taxation and

religion. The war was fought on French soil, raging off and on for more than 100 years. English

victories were followed by French victories, followed by a period of stalemate until the conflicts

again rose to the surface. During periods of truce, English and French soldiers would roam the

French countryside killing and stealing. After the battle of Agincourt in 1415, won by the English

under Henry V, the English controlled most of northern France. It appeared that England would

shortly conquer France and unite the two countries under one crown. At this crucial moment in

French history, a young and illiterate peasant girl, Joan of Arc (1412-1431) appeared and helped

rescue France. At the age of 13 Joan believed she had heard the voices of Saint Michael, Saint

Catherine and Saint Margaret bidding her rescue the French people. Believing that God had

commanded her to drive the English out of France, Joan rallied the demoralized French troops,

leading them in battle. Clad in a suit of white armour and flying her own standard she liberated

France from the English at the battle of Orleans. Ultimately captured and imprisoned by the

English, Joan was condemned as a heretic and a witch and stood trial before the Inquisition in

1431. She was found guilty and was to be burnt at the stake but at the last moment she

recanted everything. She eventually broke down again and faithful to her "voices," decided to

become a martyr and was then burnt at the stake in Rouen. Joan became a national heroine.

English and French territory during the 100 Years War

Joan of Arc

The Spanish Inquisition

Established in 1478 by Ferdinand and Isabella with the approval of Pope Sixtus IV. One of the

first (and most notorious) organizers was Tomas de Torquemada.

The official purpose of the Spanish Inquisition was to discover and punish converted Jews (and

later Muslims) who pretended to convert to Christianity for purposes of political or social

advantage and secretly practiced their former religion. Also used to investigate people accused

of being heretics. Ignatius of Loyola and Theresa of Ávila were investigated for heresy. The

censorship policy even condemned books approved by the Holy See. The Spanish Inquisition

(which was controlled by the Spanish kings) was more highly organized, cruel and freer with the

death penalty than the Medieval Inquisition in other parts of Europe; its "autos-da-fé"

(execution by burning at the stake) became notorious, as did the wide range of documented

torture devices. The Spanish government tried to establish the Inquisition in all its dominions (it

did so throughout the Spanish-controlled Americas); but in the Spanish Netherlands the local

officials did not cooperate, and the inquisitors were expelled from Naples in 1510. The

Inquisition was abolished in 1834.

Issues Facing Christians During this period

- Wycliffe remained a priest all his life, but felt that he could, and should, challenge the

system from within; this is sometimes the most effective way

- acknowledgement that it is right to understand and proclaim truth, but this can often

come at great personal cost (2 Timothy 3:12)

- strong interest in making the Bible available in the vernacular, but opposed by many in

the church hierarchy

- confusion between nationalism and the authority of religion

- men and women continued to report visions from God; some may have been genuine

- as the official church became more decadent, God raised up men and women with a

clear understanding of the Gospel, who were prepared to challenge wrong fundamentals

Additional Reading

Blainey, G, A Short History of Christianity, Viking, Melbourne, 2011

Lion, A Lion Handbook, 1990, The History of Christianity

Martines, L, Scourge and Fire: Savonarola and Renaissance Italy, 2006, Jonathan Cape, London

Miller, A, Miller's Church History: From the First to the Twentieth Century

Renwick, AM, The Story of the Church, Intervarsity Press, Edinburgh, 1973

Reid, P P, The Templars, Phoenix, London, 2003

Sackville-West, V, Saint Joan of Arc, London, The Folio Society, 2004

Ziegler, P, The Black Death, 1997, The Portfolio Society, London

German monk and writer and author of "The Imitation of Christ", possibly the best known

Christian book on devotion and outworking of Christian faith, ie learning day by day to live like

Jesus. The book is divided into four sections, three of which provide detailed spiritual

instructions: "Helpful Counsels of the Spiritual Life", "Directives for the Interior Life", "On Interior

Consolation"; the last section "On the Blessed Sacrament", is based on traditional Catholic views

about the Lord's Supper.

German monk and writer and author of "The Imitation of Christ", possibly the best known

Christian book on devotion and outworking of Christian faith, ie learning day by day to live like

Jesus. The book is divided into four sections, three of which provide detailed spiritual

instructions: "Helpful Counsels of the Spiritual Life", "Directives for the Interior Life", "On Interior

Consolation"; the last section "On the Blessed Sacrament", is based on traditional Catholic views

about the Lord's Supper.